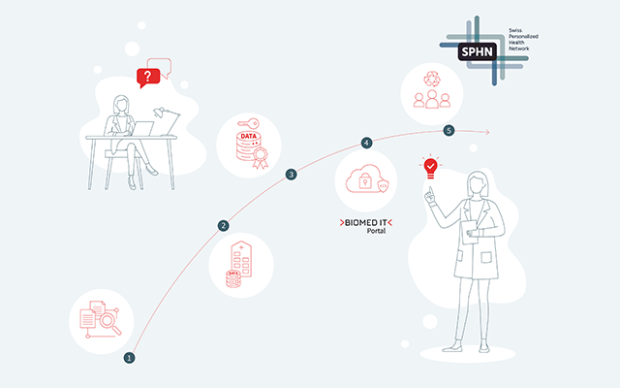

Personalized health research and derived medical innovations thrive in Switzerland thanks to a strong national infrastructure, the Swiss Personalized Health Network (SPHN). With its new 2025–2028 mandate, SPHN has now successfully entered its next phase. In this interview, SPHN’s Managing Director Thomas Geiger from the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) and Technical Director Davide Chiarugi from SIB, explain how they plan to expand services for researchers and why SPHN is considered a model for the federal government’s DigiSanté programme.

Making patient data from different hospitals interoperable for research is extremely complex. Why is it worth the effort?

Davide Chiarugi: Clinical data may be relatively unstructured at first, but once processed, it provides highly valuable, context-rich information. This enables researchers not only to better understand diseases but also the conditions under which they emerge. Studies drawing on data from multiple hospitals are more meaningful than those based on a single site. And having high-quality health data at a national level allows us to make predictions, for example, about how dangerous an infectious disease could become. In short: a great deal of effort yields substantial benefits.

About the Swiss Personalized Health Network (SPHN)

Thomas Geiger: Routine clinical data are also key to advancing personalized medicine with artificial intelligence. These models need large volumes of high-quality data. Enabling this type of research strengthens Switzerland’s position as a research hub: it builds the understanding and expertise required to apply and further develop such technologies. That’s how we ensure we can maintain a leading role in this field.

SPHN already supports researchers with legal, ethical, and technical expertise. How do you intend to further strengthen these services?

Chiarugi: Until now, we’ve focused heavily on building the infrastructure, processes, and rules for accessing the data. We are now consolidating this framework and positioning ourselves more clearly as a service provider for researchers, hospitals, and universities.

Geiger: One current project is a search platform that will show which data is available at which hospital. This will ensure that the data we have prepared over the past years can be easily found by researchers.

Until now, SPHN has directly funded research projects, but that will no longer be the case. What role will you take in supporting projects in the future?

Chiarugi: Our role is similar to that of a state that has built a railway network: the state finances the tracks, but those who want to travel by train must buy a ticket. SPHN has developed and financed the data infrastructure for research with Swiss health data. Using it now involves costs, such as for maintenance and further development, which projects will help cover in the future.

Geiger: Closer ties with the European Union also present a major opportunity. Switzerland could participate in research programs such as Horizon Europe or Digital Europe, where we can contribute our expertise to support projects.

SPHN is a federal mandate assigned to the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) and implemented jointly with SIB. How has this collaboration worked out?

Geiger: The two organizations complement each other ideally. At SPHN, we benefit from the strong trust hospitals, universities, and the federal government place in SAMS as a neutral body. One of its core strengths is building bridges – a huge asset when mediating between partners and developing governance models that fairly distribute effort and benefit.

Chiarugi: SIB, on the other hand, is extremely well connected internationally and brings great expertise in cross-border research projects. It also has a strong technical foundation and operates numerous platforms for bioinformatics research. This know-how is invaluable for our work.

At a conference last autumn, Anne Lévy, Director of the Federal Office of Public Health, said SPHN is a model for DigiSanté, the federal government’s health digitization project. What can DigiSanté learn from SPHN?

Geiger: SPHN’s success is the result of tremendous work – not only from us but also from our partners. From the start, we have focused on sustainable solutions, which meant holding countless discussions to bring all parties to a common understanding. We’ve learned that technical hurdles are almost always solvable. What really matters is governance – and, above all, the willingness of institutions to work toward a shared goal.

Chirarugi: Exactly. SPHN has shown that “difficult” does not mean “impossible.” I’m convinced that the kind of research we enable will only grow in importance for our healthcare system.