A new statistical approach published in PNAS enables the detection of inbreeding depression — the loss of fitness and overall health due to inbreeding in populations where individuals are related to one another. Led by UNIL Professor and SIB Group Leader Jérôme Goudet, the authors developed a model that can be utilized in a group of individuals with strong genetic structure. Such genetic structure can occur in endangered species with few individuals, where all individuals are related to one another or in admixed populations, where isolated populations interbreed.

Inbreeding and its consequences on health

Inbreeding is the result of mating between relatives, which can lead to increased expression of harmful genetic variants, impacting survival and reproduction rates. It is often associated with compromised health condition, a phenomenon called inbreeding depression, which has been observed in many different species, from humans and animals to plants. Measuring inbreeding and its consequences on health is central for many areas in biology including preserving biodiversity and endangered species. Developing statistical and computational methods to accurately do so are among SIB’s diverse undertakings on the biodiversity front.

Overcoming known bias

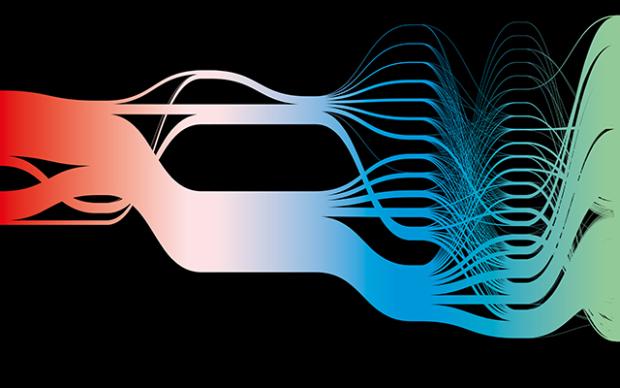

The traditional method to measure inbreeding depression works well for large and homogeneous populations, where individuals are mostly unrelated - as is the case in our own species, where countries mostly function as a large cohort of individuals. However, in groups where individuals are related to each other to varying degrees, it could lead to a biased estimation of the strength of inbreeding depression. In this study, to overcome this bias, the authors compare the classical linear regression model approach, to a mixed model that accounts for population structure by including the degree of relatedness among individuals estimated from individual genomic data. For SIB Group Leader and Associate Professor at the faculty of biology and medicine of the University of Lausanne Jérôme Goudet, this innovative method now allows “us to evaluate the detrimental effects of inbreeding where it is the most needed, in small populations from species at risk of extinction.”

Inbreeding and its consequences on health

Inbreeding is the result of mating between relatives, which can lead to increased expression of harmful genetic variants, impacting survival and reproduction rates. It is often associated with compromised health condition, a phenomenon called inbreeding depression, which has been observed in many different species, from humans and animals to plants. Measuring inbreeding and its consequences on health is central for many areas in biology including preserving biodiversity and endangered species. Developing statistical and computational methods to accurately do so are among SIB’s diverse undertakings on the biodiversity front.

Using data from the 1,000 Genomes Project

To extend their conclusions to smaller sample sizes and populations with stronger structure, such as wild and endangered species, the authors simulated traits using empirical data from phase 3 from the 1,000 Genomes Project.

By varying the groups’ size and homogeneity, the authors managed to compare their method’s efficiency for different subsamples. They then tested their model on an empirical dataset from house sparrows found in an isolated archipelago in Northwestern Norway. They were able to show that their approach is more accurate than the classical model. For Eléonore Lavanchy, PhD student in the Population Genetics and Genomics group and first author of the study “Detecting inbreeding depression in structured populations” the results show “that the method works for very small populations containing many related individuals as well as isolated populations which are more and more common because of the biodiversity crisis we are facing nowadays and where assessing the inbreeding status of individuals and its detrimental effect are crucial.”

Reference(s)

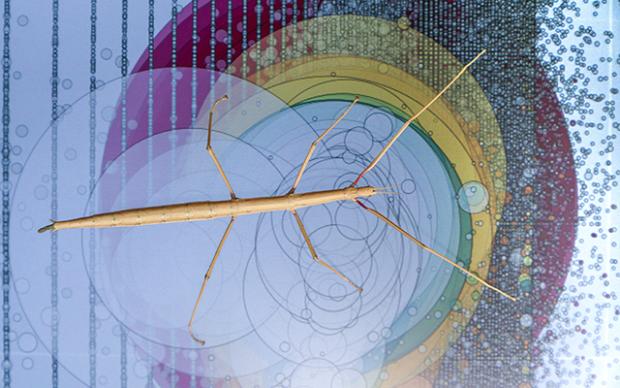

Image legend: Phenotype and genotype data of adult house sparrows were used to illustrate the method. (Joshua J. Cotton / unsplash)